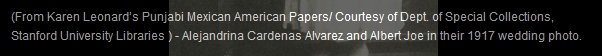

Amelia Singh Netervala points to her mother’s chicken curry enchiladas as the best metaphor for her childhood.

Born to a Punjabi Sikh father and Mexican mother, her family was full of cultural contradictions: She went to church on Sundays with her mother and three siblings while her father waited outside in the family car. She would have langar — the daily Sikh communal meal — just once a year, when her father would embark on the five-hour journey from Phoenix to the nearest Gudwara in El Centro, a Californian border town in Imperial Valley. Her clandestine conversations with her mother were done in Spanish, a language her father never mastered.

All the while Netervala never had any doubts about her identity.

“I’m proud of my Mexican heritage and mixed ethnicity,” said Netervala, who grew up on an alfalfa and cotton farm in Casa Grande, 50 miles south of Phoenix. “But if I had to choose, I would identify as being an Indian woman.”

Now in her mid 70s, Netervala is part of the nation’s thinning Punjabi-Mexican population, an identity forged out of historical necessity and made possible by uncanny cultural parallels.

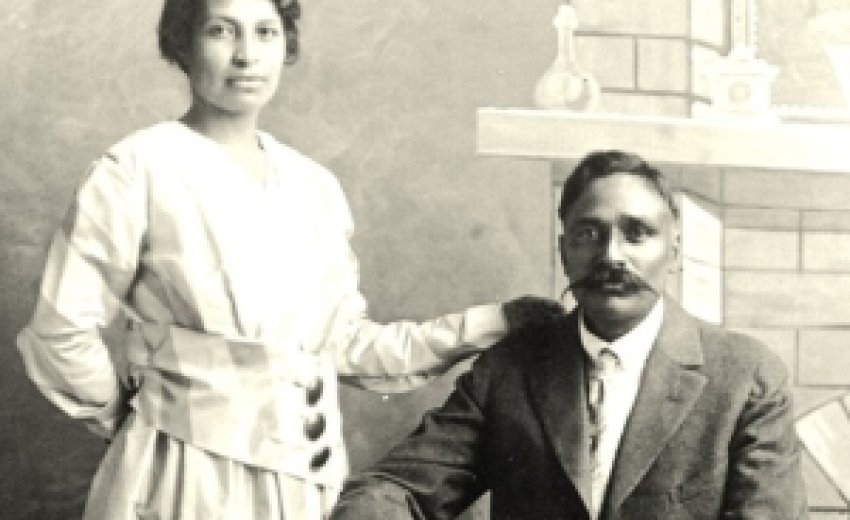

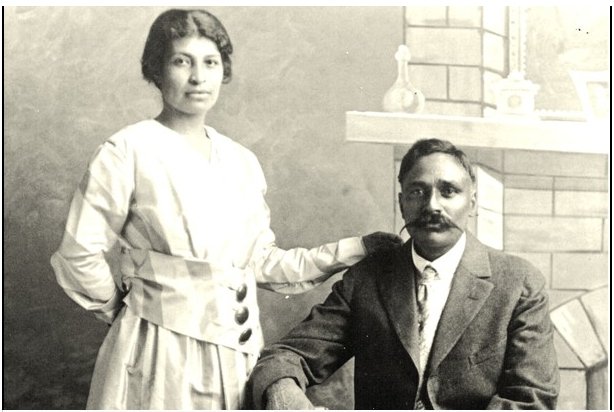

|

|

|

“The children of these unions did not marry into that community, and so now they are dying off,” explained Karen Leonard, a professor of anthropology at the UC Irvine who authored a book on California’s Punjabi-Mexican population. “So their numbers are diminishing.”

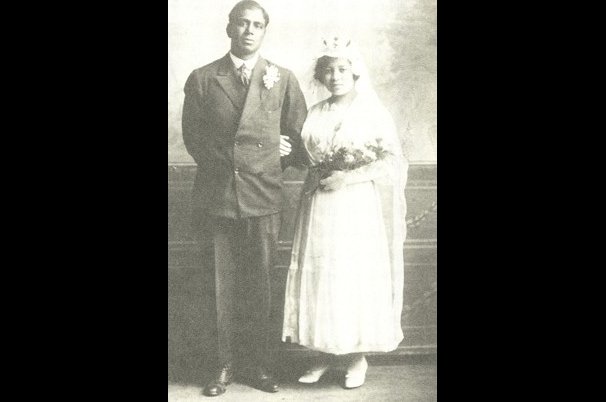

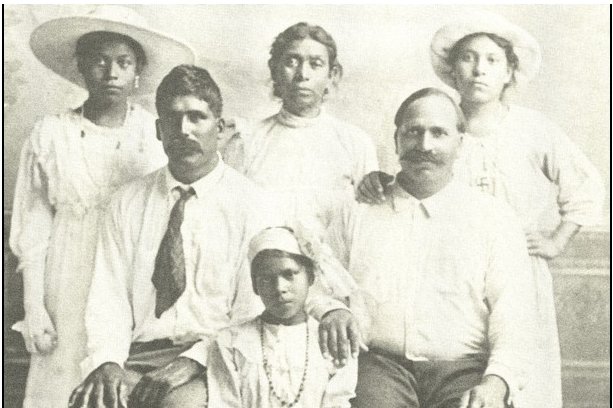

The first marriages between Punjabis and Mexican Americans occurred in the early 1900s, after waves of men from Punjab — a geographic region straddling the Indian-Pakistani border — immigrated to the United States by way of Canada.

Although their numbers were initially small, estimated in the few thousands, the Punjabis, who were mostly Sikh, quickly adapted to life in the farming communities of the United States, particularly in California’s Central and Imperial Valleys. Drawing on their extensive agricultural knowledge, the Punjabis planted troves of peach and prune orchards, which today produce 95 percent of the peaches and 60 percent the prunes that grow in Yuba-Sutter County, an fertile agricultural hub California’s Central Valley.

Despite their contributions to California’s farming industry, early Punjabi immigrants were heavily discriminated against both economically and socially, said Vinay Lal, a professor of history at UCLA.

The California Alien Land Act of 1913 prevented all “aliens ineligible for citizenship” in the state to own agricultural land. And although the act primarily targeted wealthy Japanese landowners in California, the Punjabis were not considered citizens and were victimized, Leonard said.

Strict immigrant laws also prevented Punjabis living in the United States from bringing wives from India, creating a distinct problem for the community.

“They would have gone to India to find brides and brought them back,” Lal said. “But when they passed the Asian Exclusion laws, it became impossible for them to leave.”

Traditionally, Punjabis had marriages arranged by their families. But facing strict immigrant quota laws, the then-newly immigrated Punjabis — overwhelming majorities of whom, according to Leonard, were Sikh, at nearly 85 percent — were forced to turn elsewhere.